Current Issue

Previous Issues

Spring 2025. Issue 1541

Winter 2024. 1540

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Spring 2022. 1530.

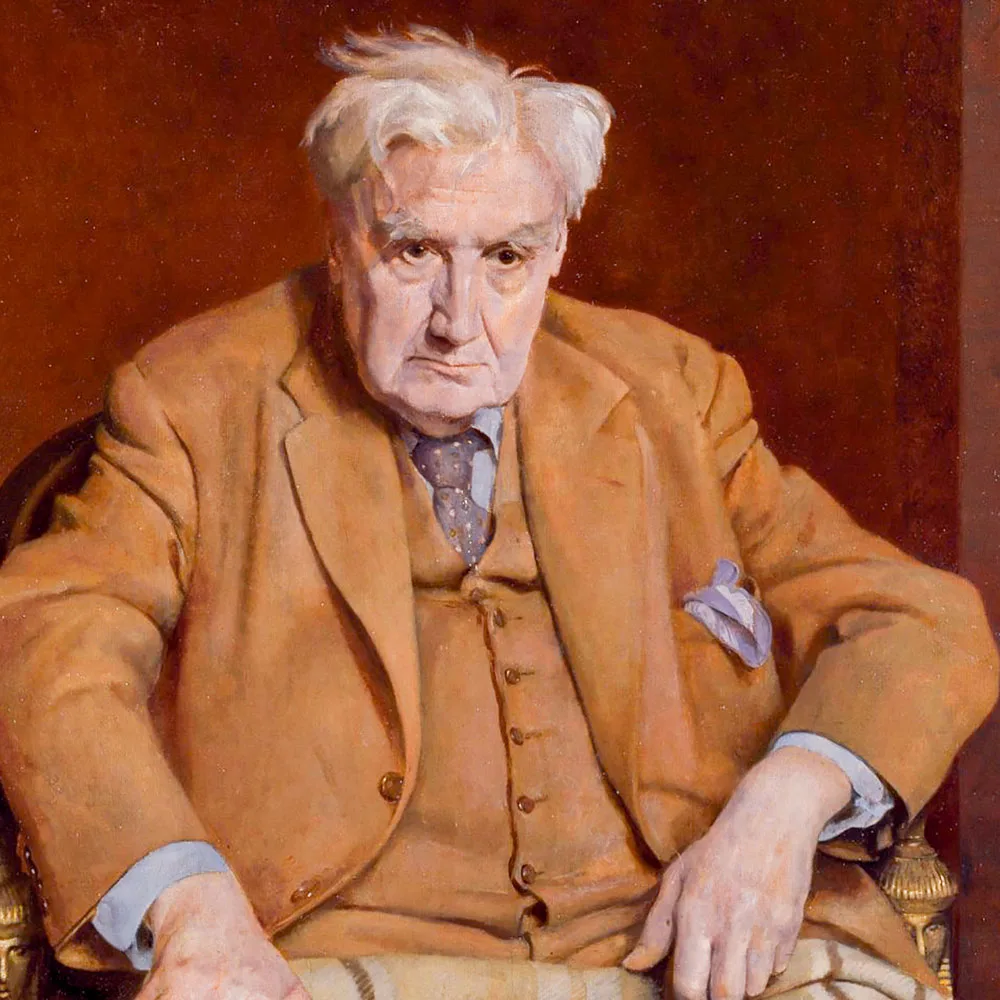

Music to ‘chase fatigue and fear’: Ralph Vaughan Williams – A Double Celebration in 2022

Stephen Connock

Marking two significant anniversaries for Ralph Vaughan Williams – his 150th birth year and the centenary of the first performance of his moving war-inspired Pastoral Symphony.

The 150th anniversary of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s birth falls on 12 October 2022 which provides a timely opportunity to reflect on the composer’s stature, nationally and internationally, and to consider the relevance and importance of his music today.

It was fortunate that Vaughan Williams’s centenary in 1972 had Sir Adrian Boult taking the lead, conducting many of the symphonies, especially Nos. 2, 5 and 8, along with a memorable Job. There were also fresh and lyrical performances of Hugh the Drover, produced by Dennis Arundell, in June that year at the Royal College of Music, and a series of five concerts conducted by Donald Cashmore at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, with highlights including Epithalamion, Pilgrim’s Journey and Hodie. A youthful André Previn conducted A London Symphony at the Royal Festival Hall on 26 September 1972 and told us: ‘I don’t think there is a worry in the world that Vaughan Williams is a world figure’.

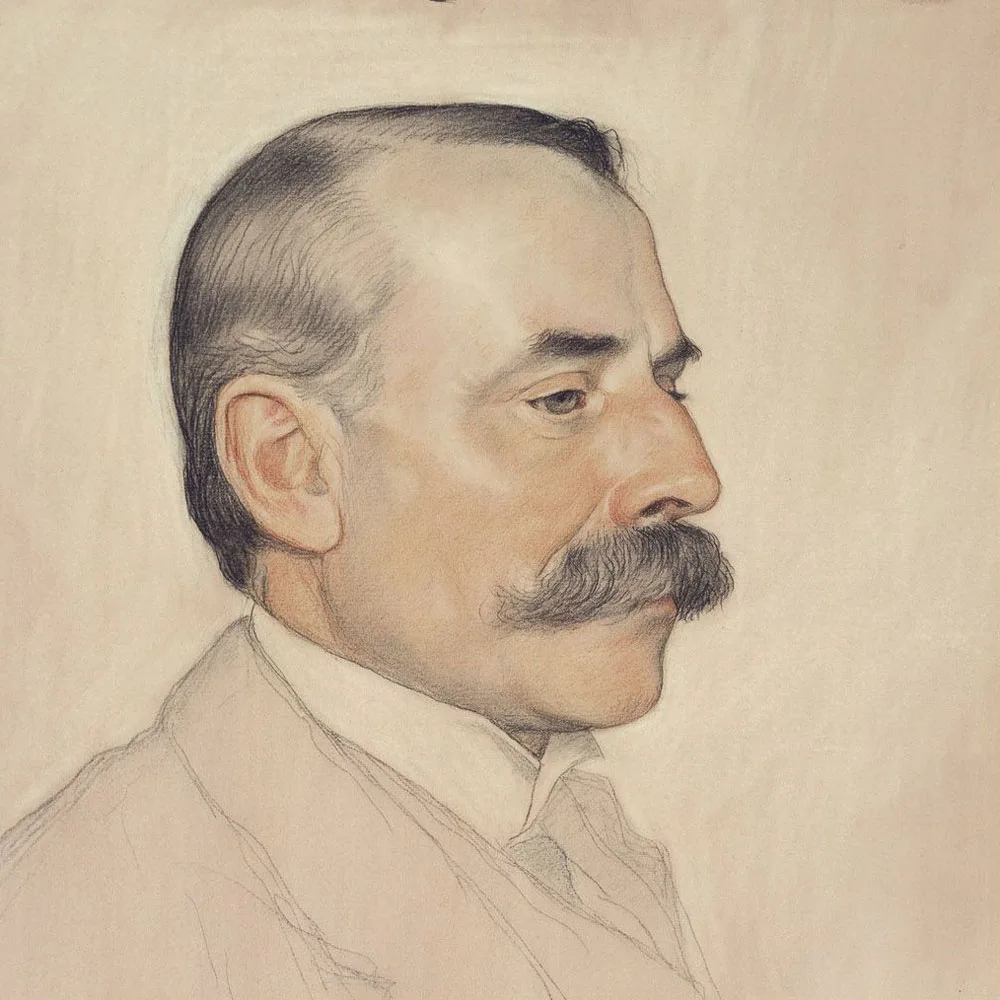

Elgar and his Transcribers

Tom Higgins

During Elgar’s lifetime his fame was enhanced through the expertise of transcribers who ensured his music reached a wider audience.

Soon it will be 100 years since Dan Godfrey (1868-1939) was knighted ‘for valuable services to British music’. His ‘valuable services’ were identified as the part he played in the success of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra – he founded it, gave it a policy of championing British music and by the early 1920s had directed it for 30 years. Posterity decrees that Godfrey is best remembered as the conductor who brought high-level music-making to Britain’s south coast. To raise a municipal ensemble to the status of a leading orchestra would have been enough for most conductors, but Godfrey was too talented to concentrate on one thing.

Beneath his public position lay a skill which he shared with a number of contemporaries. During Godfrey’s early career his name began to appear regularly on military band versions of orchestral works. In company with other experienced arrangers, he received commissions from publishers to take popular works from the concert hall and produce transcriptions for bands. Their knowledge of wind band instrumentation was exceptional and ensured that the original music retained its integrity and could be played by a band without loss of quality.

Peter Dickinson – Words on Music

An interview on his life and work with Tom Service of the BBC

TS It’s a little invidious to attempt to sum up at least a fourfold career as writer, performer, university teacher and of course composer. One of the things that strikes me in Words and Music is where all this might have come from. Was it obvious that you were going to pursue this kind of life in music?

PD I don’t think it was. Things came out of my interests like finding sheet music of Satie and Lennox Berkeley in the Cambridge music shop when I was at school. I didn’t know any other music like that and it was a revelation. A different way of making music from all the academic studies we had to do at Cambridge.

TS These encounters inspired a very particular canon of interests. As much Virgil Thomson and Billy Mayerl as Bach and everybody else. Also Lord Berners.

PD Cage too – meeting him around 1960 when nobody in England was taking him seriously. Because I met him I did. He was just a wonderful human being. That created my enthusiasm for what he was doing even if I didn’t go all the way with him, as you can tell from my music. But I owe a lot to those Cage pieces which put together all kinds of stuff. My bigger works are assemblies composing with three or four different strands of music. Then I let some of the separate ingredients have their own lives so that a rag out of the Piano Concerto has been recorded as a piano solo. So has a blues take-off of Edward MacDowell’s To a Wild Rose. This confused people. Was I trying to be popular?

The Music of Peter Wishart

Richard Carder

Many choral singers will recall Peter Wishart’s most well-known carol, Alleluya, a new work is come on hand, which has been recorded several times, and is published in 100 Carols for Choirs (OUP), a fast and lively piece in compound time with a chorus of overlapping bell-like Alleluyas for the female voices. The words are from the 15th century, and originally formed one of Three Carols written for the Birmingham Singer’s Club in 1952. The other two in the set are There is no rose of such virtue, and Lullay, my dear mother, also with old words, and more complex harmonies.

The only other recorded choral piece, on a CD entitled, 20th Century Masters, Volume 2, for Avie, by the choir of New College, Oxford, under Edward Higginbottom, is the anthem, Jesu, Dulcis Memoria, composed in 1968, when Wishart was based in London, teaching at the Guildhall School of Music. The words again are medieval from the 14th century: Jesu, sweet is the love of Thee, None other thing so sweet may be, Nothing that men may hear and see Hath no sweetness against Thee. Four more verses follow this in devotional mode, remembering the crucifixion with painful harmonies.